(Get free painting tips and plein air painting techniques sent straight to your inbox or on my social media.)

What Is Linear Perspective In Art?

Linear perspective is a set of rules that you can use to predict how three-dimensional objects will appear on a two-dimensional surface depending on how far away they are from the viewer. It is based a the visual effect that all parallel lines appear to merge to a single point. If these lines are horizontal, that point will be on the horizon. Atmospheric perspective on the other hand deals with how the atmosphere changes the color of objects as they move into the distance.

Learning how to use linear perspective is very important when painting interiors and streetscapes, but it is also useful when painting landscapes, still lifes, and even when painting figures and portraits.

Perspective Lines And Vanishing Points

Although there are three types of perspective, there is one that is most commonly used in landscape painting. This is called one-point perspective. Two-point and three-point perspective are used in more complex architectural subjects and city scapes. In one point perspective, all the horizontal lines on a single plane converge at a single point on the horizon.

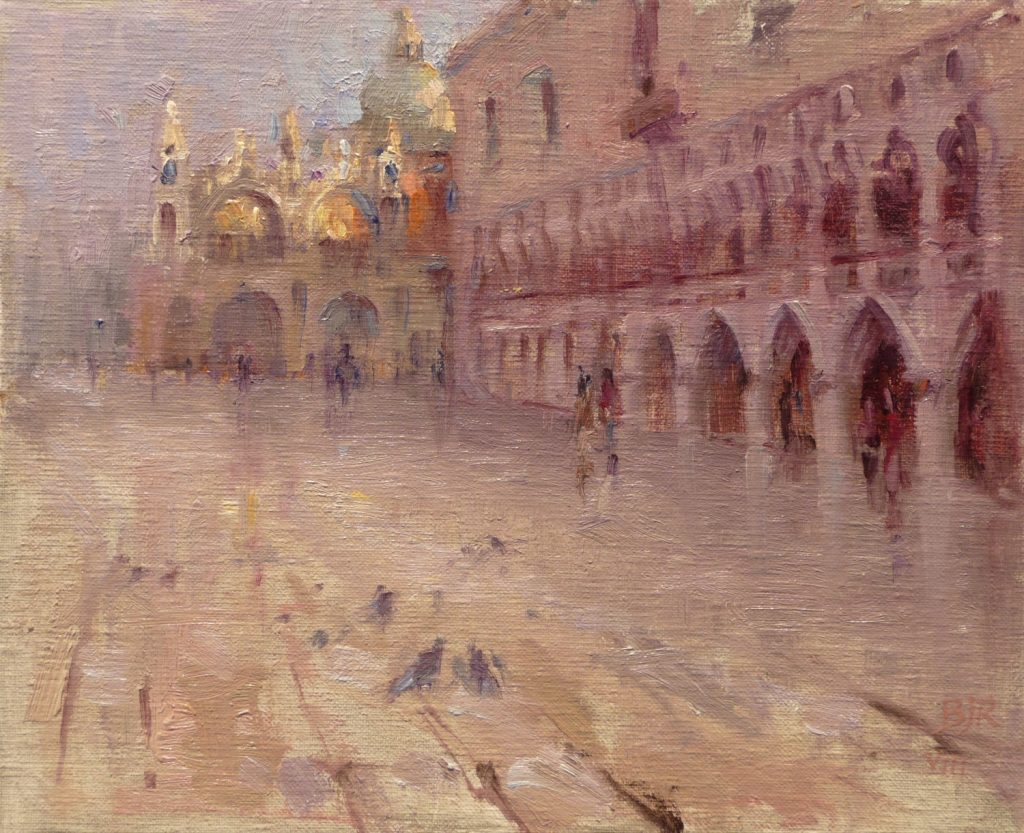

I painted this just as dawn was breaking in St Marks Square, Venice. The building on the right is the Doge’s Palace and the church in the background is the famous Basilica of St Marks.

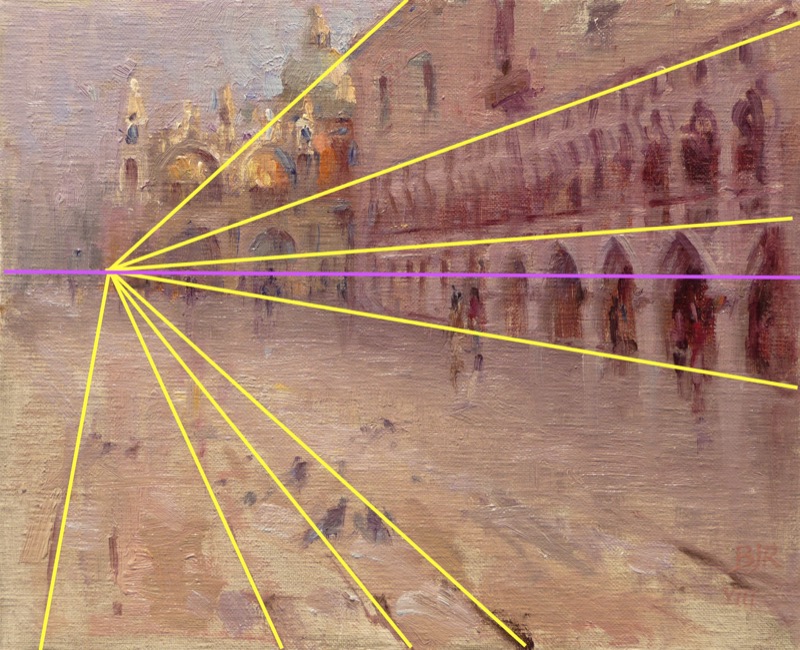

Even when you are painting in a fairly free and impressionistic style as I am doing here, there are certain lines that you need to draw very accurately in order to give a good sense of depth to your painting. This will also help to make the scene look real. In this painting the most important lines that need to be accurate are the perspective lines on the wall of the Dodge’s palace. This is an example of the use of two point-perspective (only one vanishing point is shown).

Since the wall we see on the right is in a single plane, all the horizontal lines on that plane will converge to a single point. This point is called the vanishing point. If the lines are horizontal as in this example, this point will always be on the horizon line for the viewer.

In this diagram you can see the horizon line in purple, and all the perspective lines are in yellow.

Brushwork And Linear Perspective

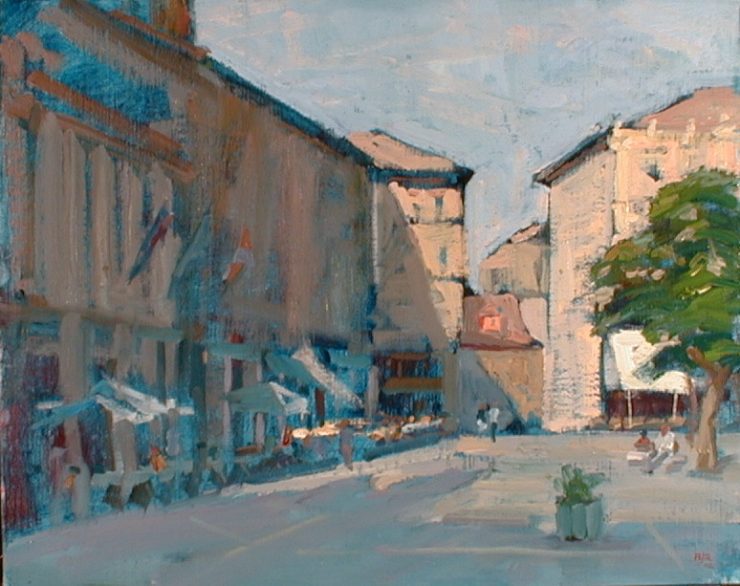

You do not always have a building to show the depth in the painting. Sometimes you just have a flat ground plane. However you can use expressive brush work in order to emphasize the sense of depth in the painting as I have done here.

In this detail of the painting you can see I have used thick brush strokes painted in the direction of the perspective lines in the foreground. The direction of these strokes and size give the impression of linear perspective and give depth to the painting. At the same time they add an expressive quality to the painting.

History Of Linear Perspective In Art

It was not until the 14th century that linear perspective began to be used by artists to be able to create a realistic representation of our three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. For example, the figures in ancient Egyptian drawings and paintings are usually shown in profile, while their eyes are shown facing the viewer.

FAQ

What Are The Three Types Of Linear Perspective?

There are three types of linear perspective. These are: one point, two point, and three point perspective. In these systems, there are one, two, and three vanishing points respectively. The system most commonly used is one point perspective in which all the lines of perspective converge upon a single point.

There are other types of perspective other than linear perspective, such as parallel perspective, but these are more used in mechanical drawing than artistic drawing.

Thank You

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. I hope you find it useful. If you would like to get free painting tips by email, please sign up for my free tips newsletter.

If you are interested in a structured approach for learning how to paint, take a look at my online painting classes.

Happy painting!

Barry John Raybould

Virtual Art Academy

“If the lines are not horizontal (in other words, not parallel to the flat ground), the lines will meet at a vanishing point that is either above or below the horizon line.”

Ah, I think I’m with you now. When you say “not horizontal”, you mean not horizontal *in reality* (as opposed to how they appear in the picture plane).

For example, the converging (vertical) lines at the front of a high-rise building, when you’re standing at the bottom of it, would hit a vanishing point well above the horizon line.

Thanks for the explanation, Barry.

Hi, Barry.

I’m a little confused by the example in the middle. You’ve said it’s two-point perspective, but you’ve only marked up one vanishing point. Are you referring to the fact that there’s also a vanishing point outside the picture plane to the right?

Also, you’ve said, “In one point perspective, all the *horizontal* lines on a single plane converge at a single point on the horizon.”

I wonder if you meant to say “all the parallel lines” rather than “horizontal lines”. I’m just thinking of the classic example of one-point perspective where you’re looking down a road that recedes into the distance. In that case, the lines on the ground plane can look more vertical than horizontal.

Yes, you are correct. The second vanishing point, is out of the picture in the Venice scene that I chose to paint. So although this scene was a case of two point perspective, you cannot see the other vanishing point as it was not important in the composition.

With regards to horizontal lines in linear perspective, converging at a point on the horizon, that is correct. If the lines are not horizontal (in other words, not parallel to the flat ground), the lines will meet at a vanishing point that is either above or below the horizon line. The lines are in reality horizontal, but of course they will appear to the eye to be almost vertical if the vanishing point is nearly straight in front of you.

Thank you this so helpful and important

Thank you Barry. That was interesting.