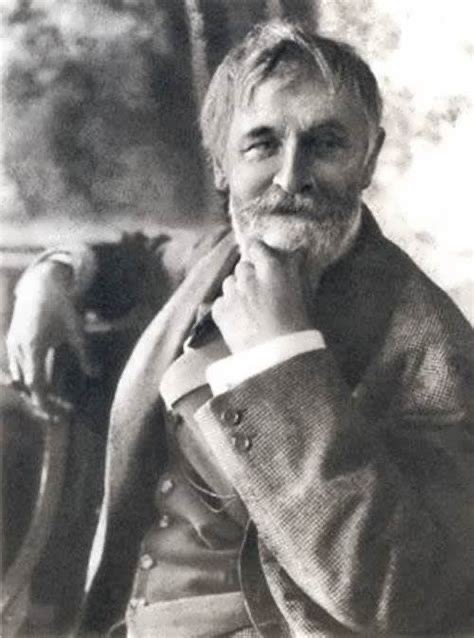

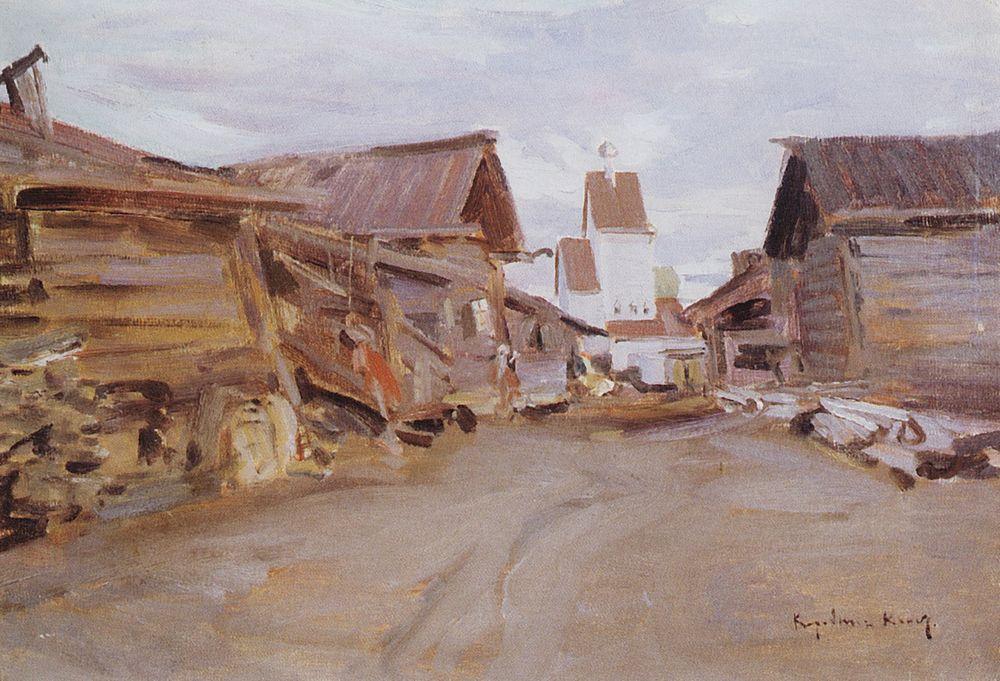

Konstantin Korovin: The First Russian Impressionist?

Konstantinos Korovin wanted to be remembered as the “First Russian Impressionist”. Although he has as much right to that title as anyone, it was as a stage designer for the theatre and opera that he made his biggest contribution to art history. He was the first to use staging and costume as a way to express the mood and characters of the performance, not just as background to the action. Think of the “Star Wars” movie. The scenery props and costumes are as central to the experience as the plot or dialogue. Korovin is responsible for that way of thinking about stage design. So why would an artist base his reputation on being a follower of the impressionists rather than a leader in the art of stage design? For the answer you have to look to the nineteenth century art world in Russia, and in Paris.

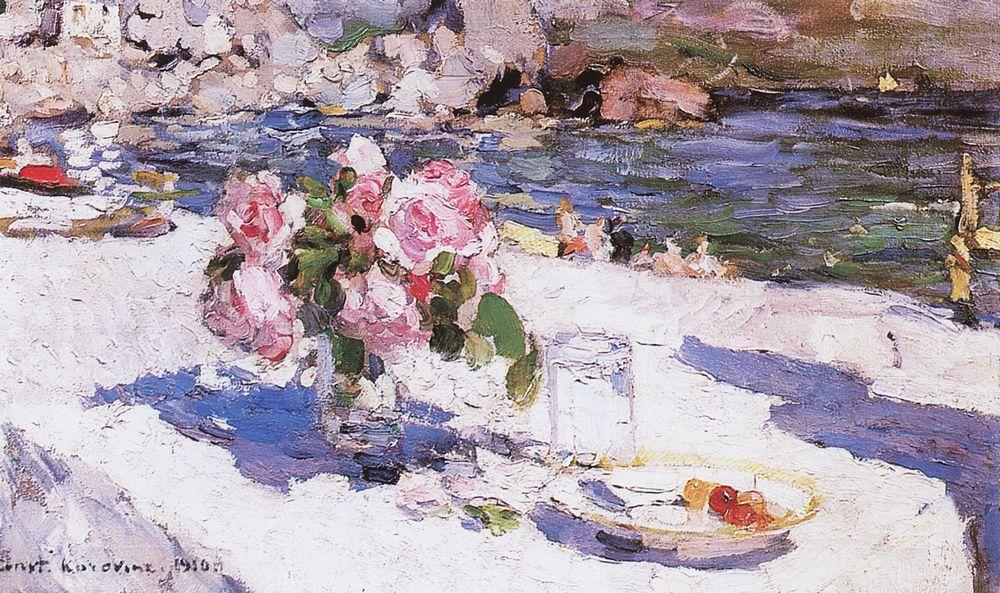

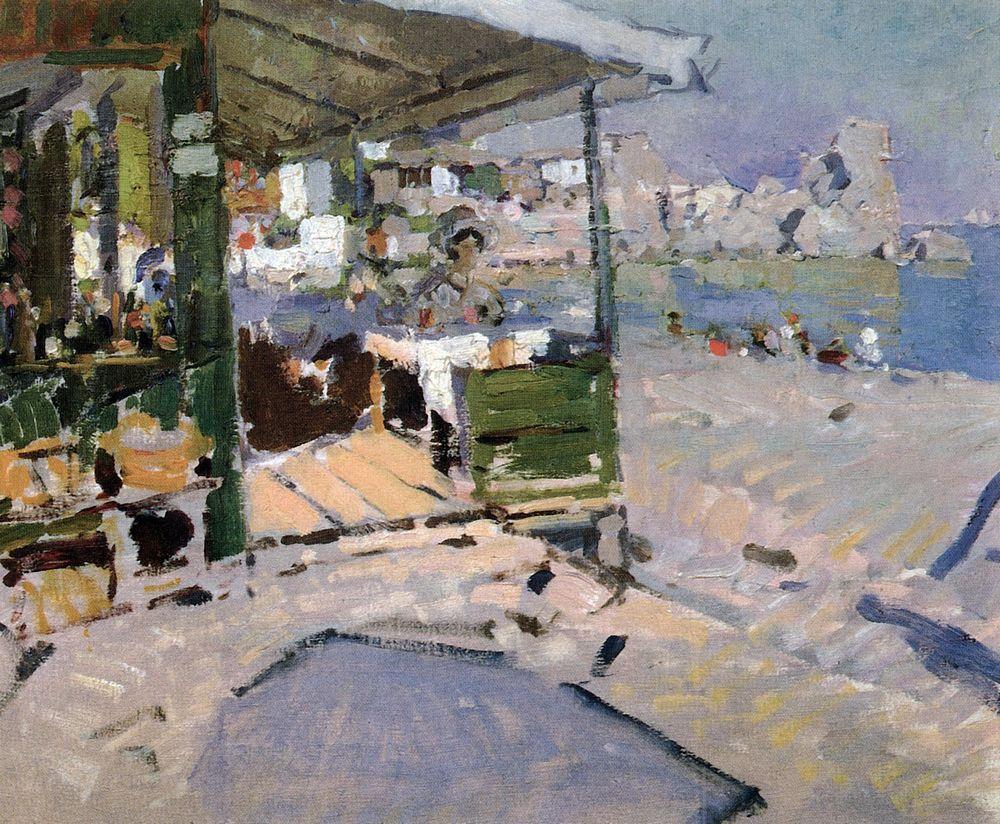

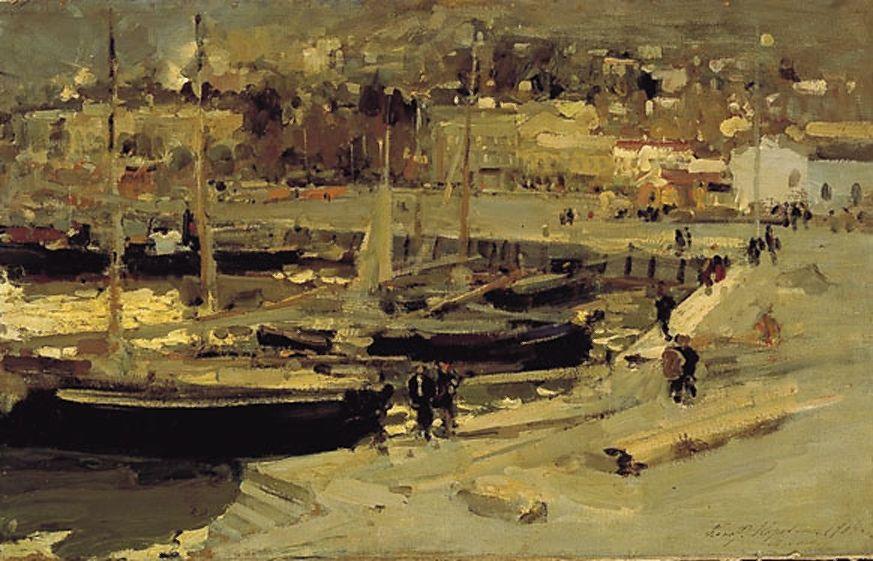

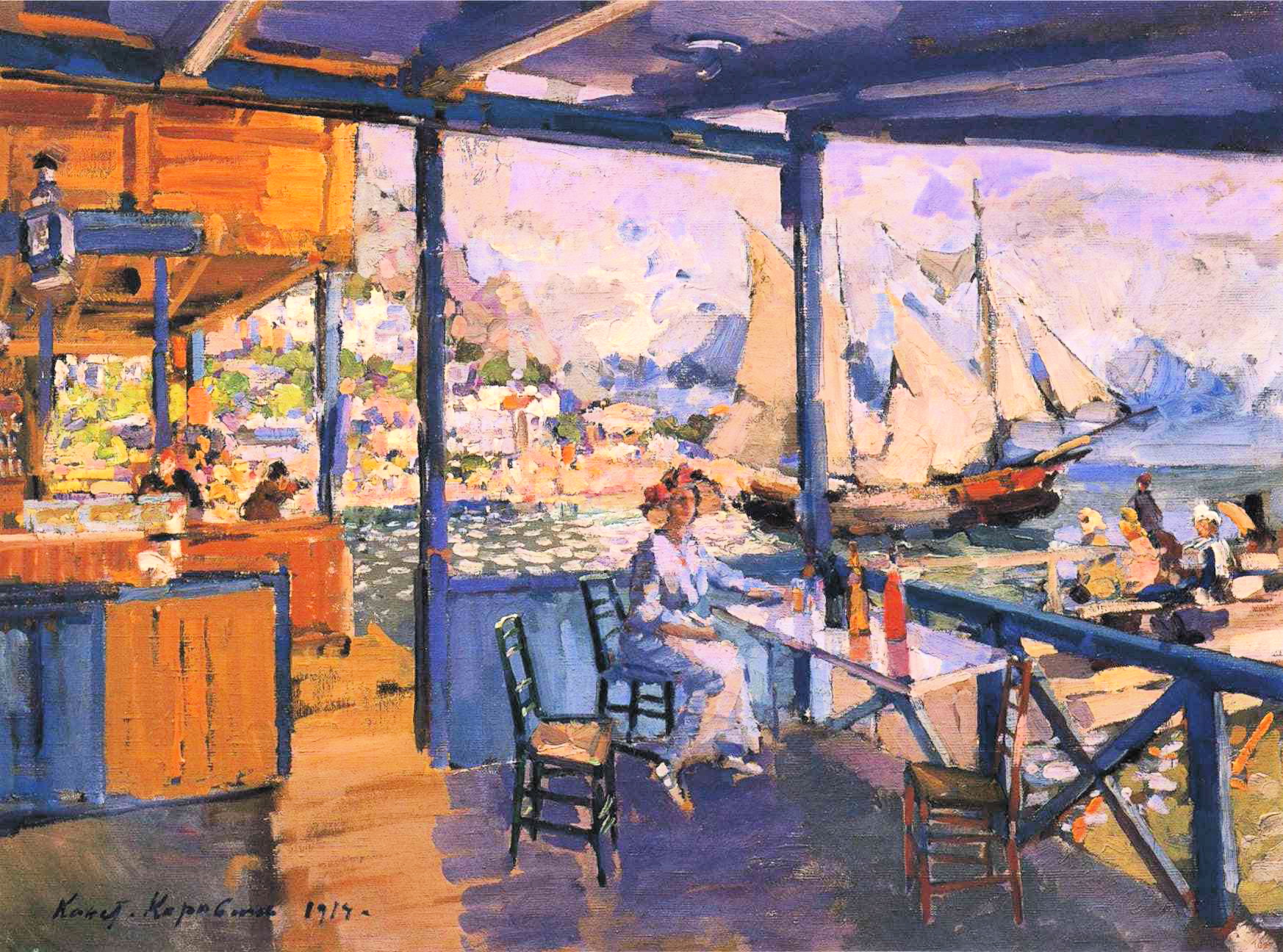

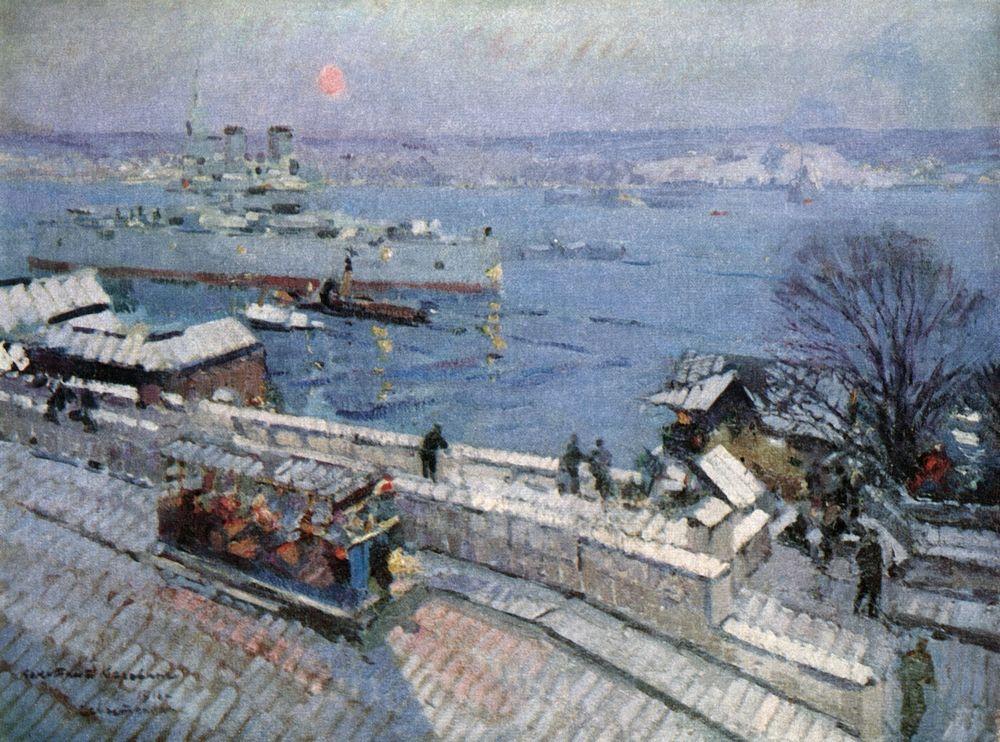

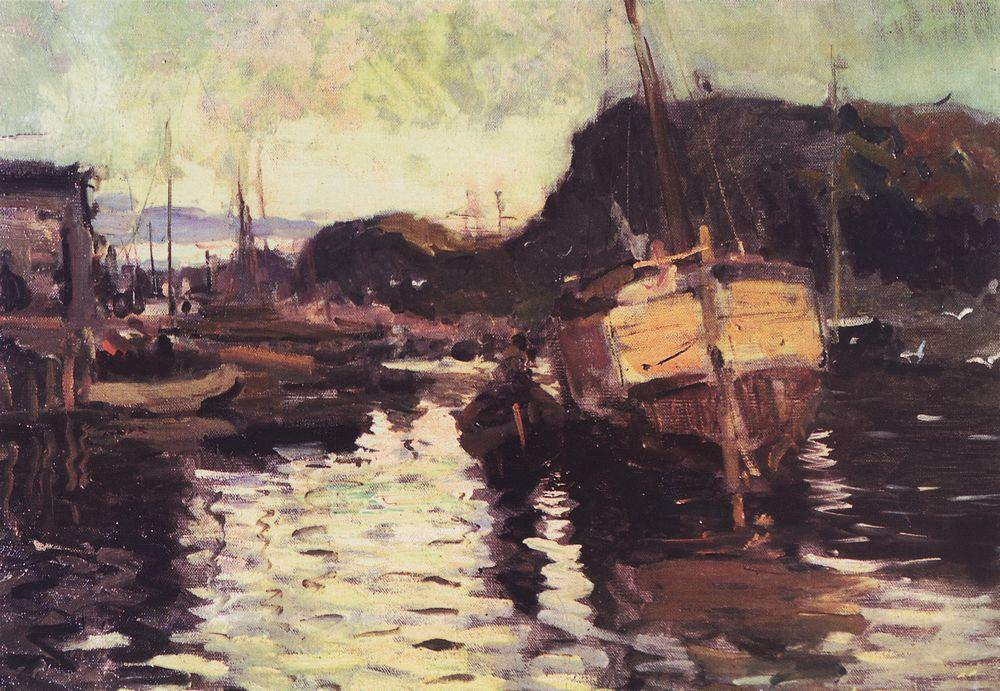

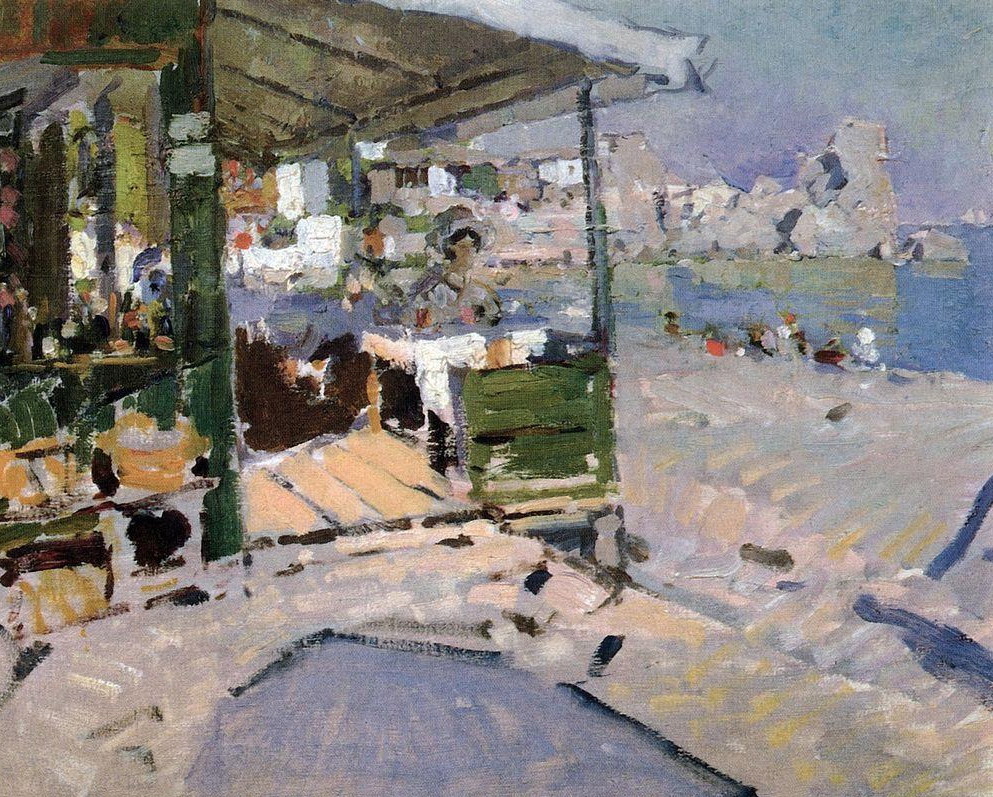

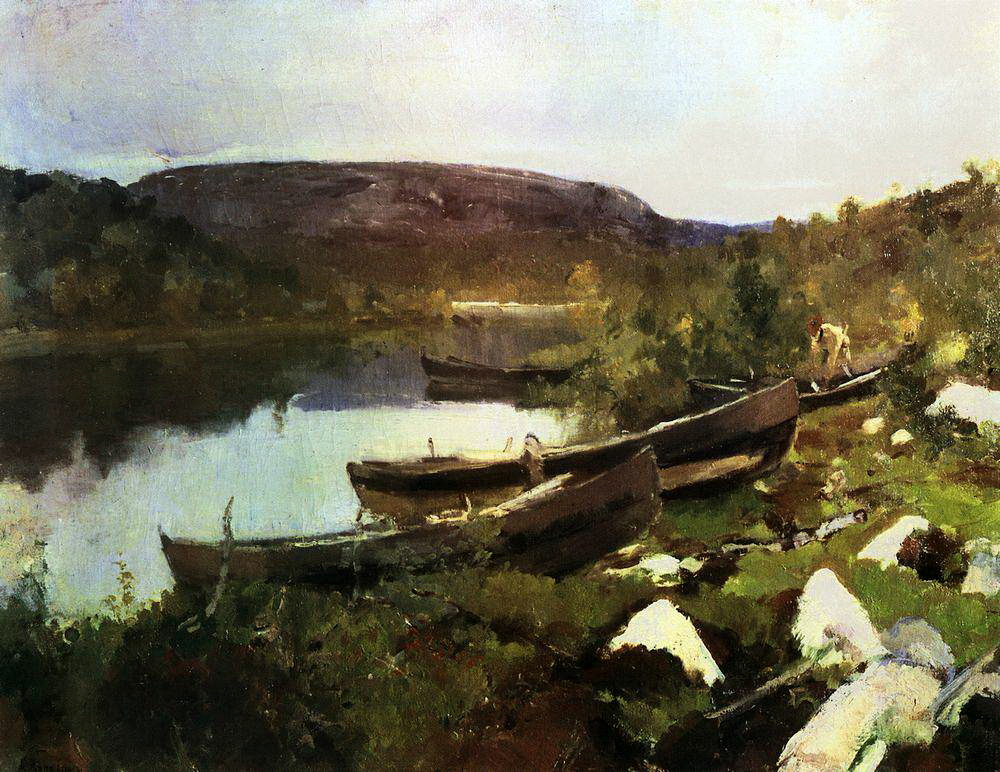

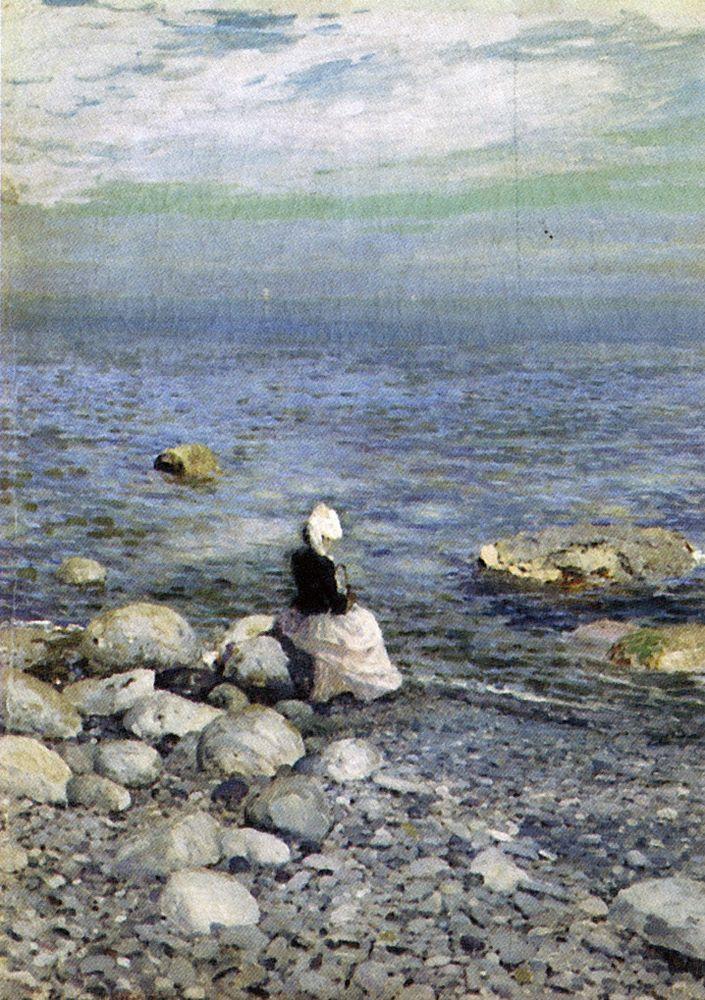

Konstantin Korovin – Seascapes

Birth and Early Life

Konstantin Korovin was born in Moscow on 5 December 1861, except his family would record it as 23 November because Russia still used the Julien Calendar. Western Europe had adopted the more accurate Gregorian calendar in 1582. Russia in the 19th Century was quite literally, behind the times. Eighteen sixty one was also the year Tsar Alexander II emancipated the serfs. (Actually it was more complicated than that but 1861 is the iconic date.)

Serfdom in Russia can be distinguished from the chattel slavery that existed in the U.S. at the time (the U.S. Civil War also began in 1861), in that serfs were nominally bound to the land and could only be sold with it. There were exceptions, and in practice many serfs were landless. They were used by their landowners as household servants or, increasingly, as factory workers. When Konstantin was born, close to 40% of the Russian population were serfs. Some though had become prosperous and even held title to serfs of their own, and many had purchased their freedom. A few, such as the Korovins had become wealthy merchants.

The Tsars had to work hard to keep control of their people, and to that end had established a massive bureaucracy and record keeping system. Thus it was that the Korovin family, while living as prosperous merchants in Moscow, were registered as, “Peasants of the Vladimir Gubernia”. A Gubernia was an administrative region. Vladimir is a city about 185 km east of Moscow. Registration status was hereditary and based on the status of the husband. Registration status often remained the same, despite changes in social status and residence. There was a bureaucratic procedure for updating one’s registration, but it was expensive and time consuming. Especially after emancipation of the serfs, it really didn’t matter and few people bothered.

Hard Times and Education

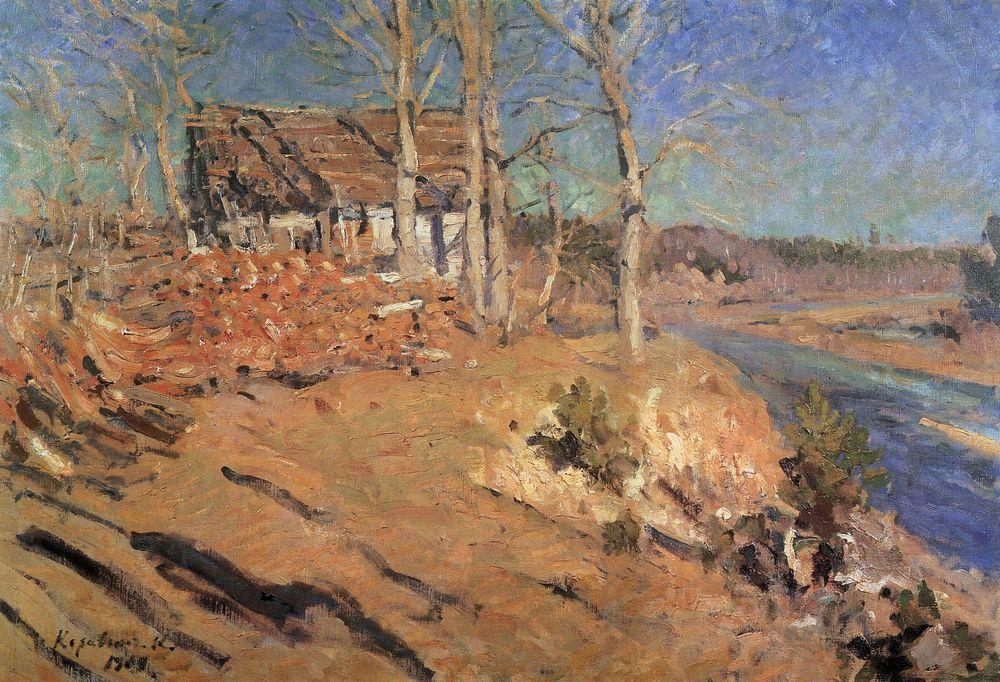

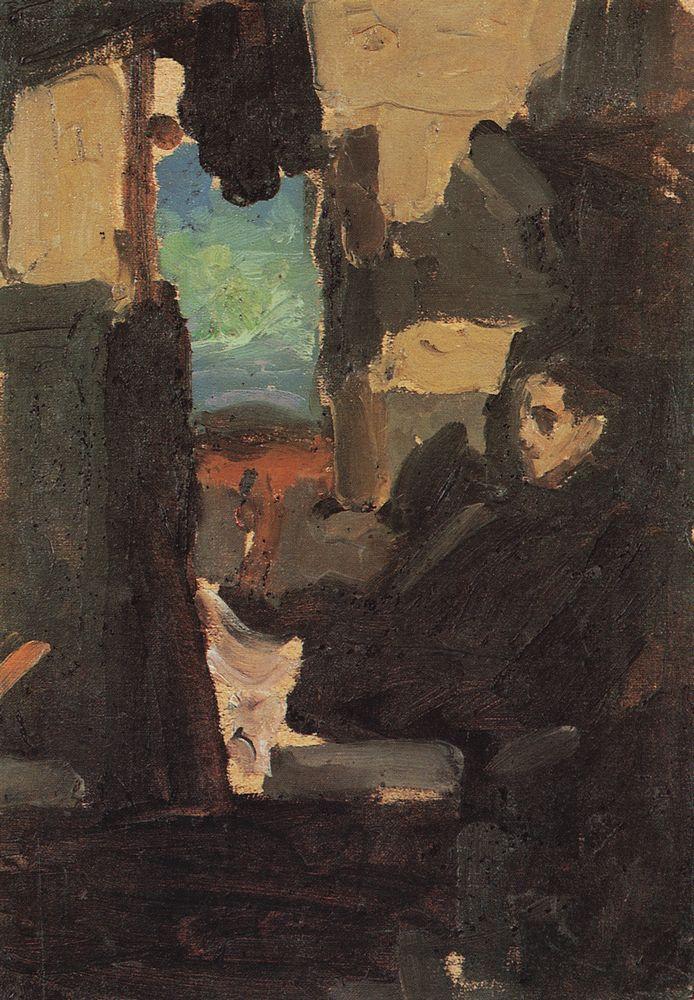

It was Konstantin’s grandfather who started the business and allowed his father, Aleksey Mikhailovich Korovin to obtain a university degree and develop an interest in Art and Music. Konstantin also had an older brother, Sergei who shared their father’s interest in Art, and became a noted realist painter. Unfortunately no one seemed to inherit grandfather Korovin’s head for business and the family fell on hard times during Konstantin’s childhood, and had to move to a rural suburb outside Moscow.

The family was still able to send the brothers to the “Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture”, possibly helped by their relative Illarion Pryanishniker a painter and teacher at the school. Konstantin entered the school at the age of 14 in 1875 in the footsteps of his brother. Besides Prynishnikor, their teachers included Vasily Perot, Alex Saurasor and Vasily Polenov. They joined an illustrious group of fellow students including Valentin Saurasov, and Isaac Levitan. Konstantin kept in touch with these friends for the rest of his life.

The Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture was one of the two most prestigious art schools in Russia, The other was “The Imperial Academy of Arts” in St. Petersburg. Konstantin also attended there for a year when he was 20 in 1881-1882, but returned to Moscow where he continued his studies until 1886. That’s eleven years of art education. The Descendent of the Imperial Academy still exists in St. Petersburg and maintains a daunting classical curriculum modeled after the 19th century version of the “École des Beaux Arts” in Paris. Jean Leon Gérôme would feel at home there.

Marriage and Tragedy

In 1886 he married Anna Yakovleyna Fidler. It has been suggested that the marriage was not a happy one. It was certainly marred by tragedy. Their first child died in childhood, and their surviving son Alexey (b. 1897) was injured at the age of 16 in a streetcar accident and lost both his feet. Alexey required continuing medical treatments for the rest of his life. He eventually build an art career of his own in imitation of his fathers style.

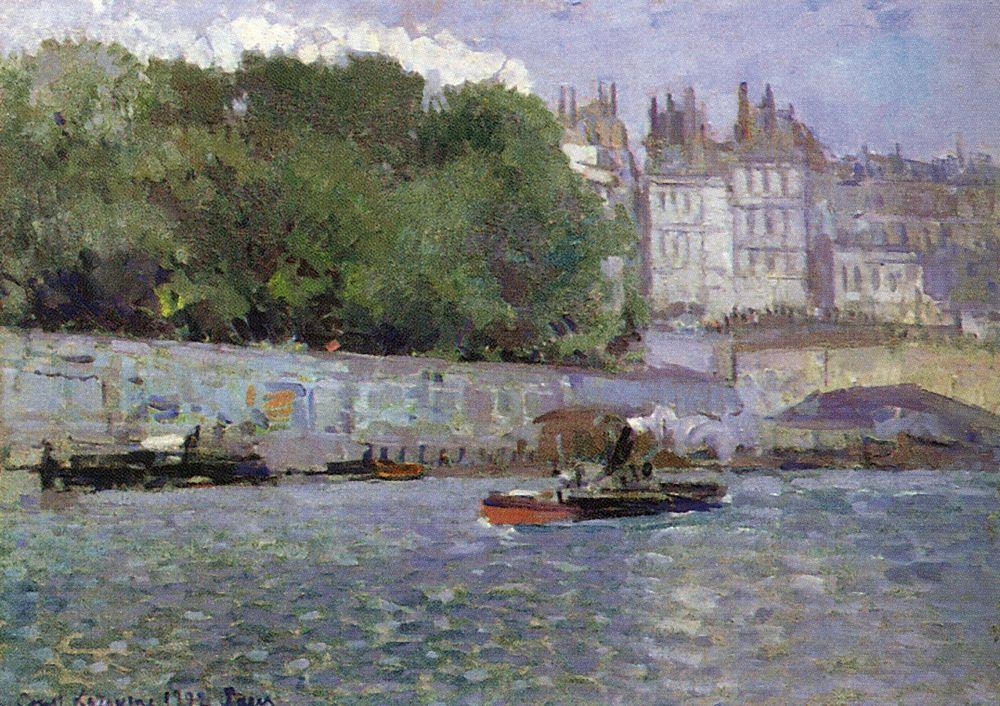

After He Saw Paris

It is impossible to understate the cultural impact of Paris in the 19th Century. If you were a cultured Russian; you read French literature, dressed in French fashions, ate French food, listened to French music, and in the upper levels of society spoke French at home. Russian was reserved for speaking with servants or tradesmen. In 1885 though Impressionism was not in the mainstream of the French art world. The Salon catalog for that year is full of academic paintings and sculpture with little evidence of Impressionism. Although Emile Zola had been writing about the Impressionists in a Russian magazine since 1871, the movement was not well known in Russia. Perhaps because Zola was not really a fan. He thought their ideas promising but not yet developed.

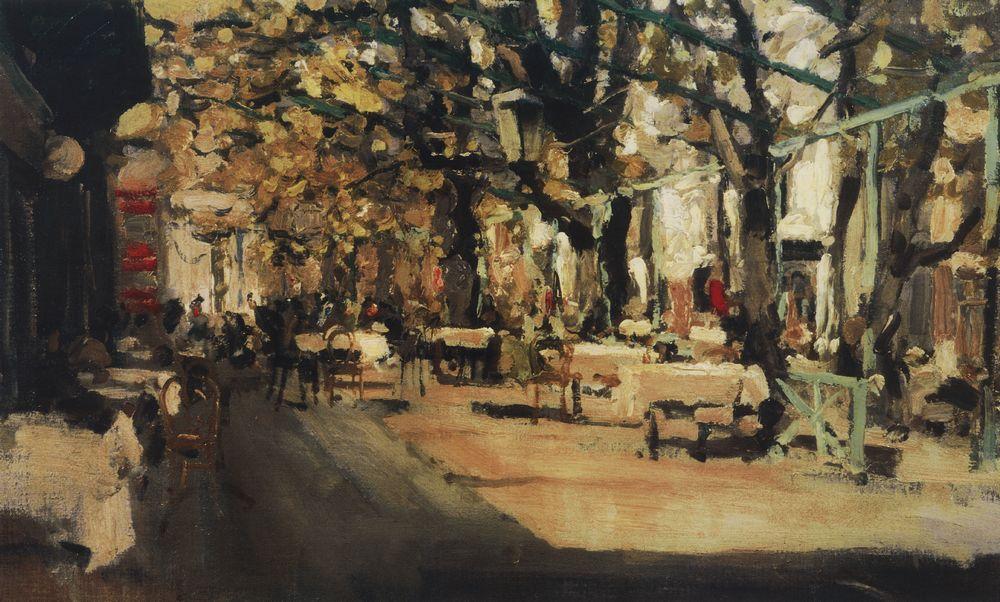

Konstantin visited Paris for the first time in 1885. By then the Impressionist movement was no longer young. Louis Leroy, the man who had coined the term “Impressionism” in a disparaging review of the “Salon des Refuses” died in that year and the last explicitly Impressionist exhibition was held in 1882. Manet had died the previous year. August Renoir said that by then (1885) “he had wrung Impressionism dry” and produced “Girl with a Hoop” in what he called his “Aigre” (sour) style e phasing clarity of form and expressive brushwork. The Impressionists were no longer the lead element of the Avant Guarde.

That is not to say that the Parisian art world was not still an exciting and vibrant place. The first “Salon Des Indépendants” had opened in December 1884, a landmark in the development of what would be known as “Post Impressionism”. Seurat was working on “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte”. Paul Gauguin had just returned from Copenhagen and was trying to reconcile with his wife. Cezanne exhibited “the Bather” Van Gogh was in town mourning the death of his father.

Impressionism, of course, was far from over. Monet was in Giverny painting haystacks, and if Konstantin had stopped in the Cafe Mirliton he would have seen Toulouse Lautrec’s paintings on exhibit.

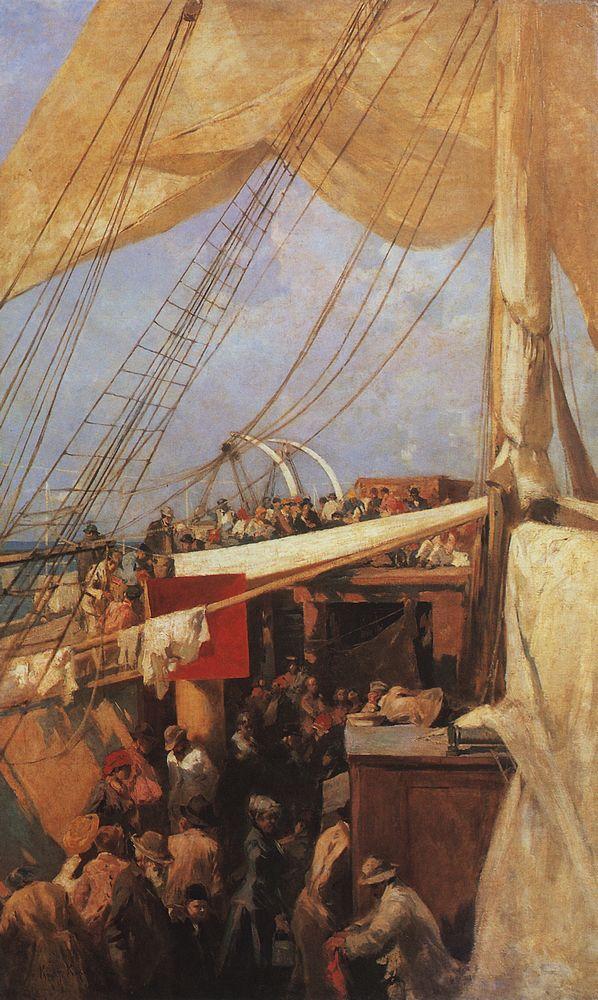

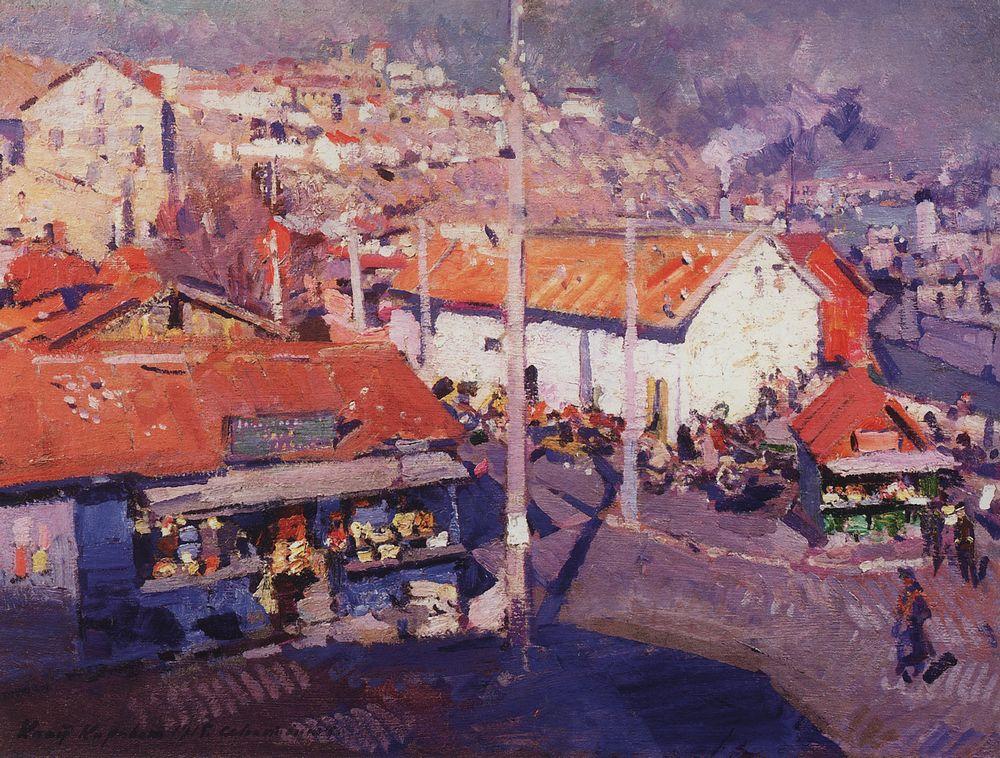

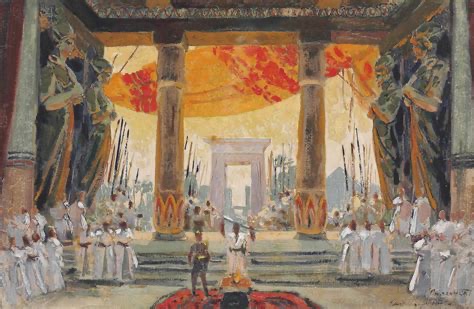

Moscow and the theatre

Cutting edge or not Konstantin was bowled over by the Impressionists. He first visited Paris in 1885. He said that, “Paris was a school for me.” Speaking of the Impressionists he wrote, “ …in them I found everything I was scolded for back home in Moscow.” He enthusiastically began to incorporate Impressionist ideas into his own work and advocate for the style bank home. He was introduced to the Abrantsevo Colony. This was an artist’s colony located on an estate in the suburbs of Moscow. By 1885 is was owned by Savva Mamontov,, a wealthy patron of the arts. Analogous to the English Arts and Crafts movement the Abraamtsevo artists emphasized Slavic themes, traditional craftsmanship and folklore. Mamontov also ran an opera house where he launched Konstantin’s theatre career commissioning him to produce sets for Verdi’s Aida, Bizet’s Carmen and others.

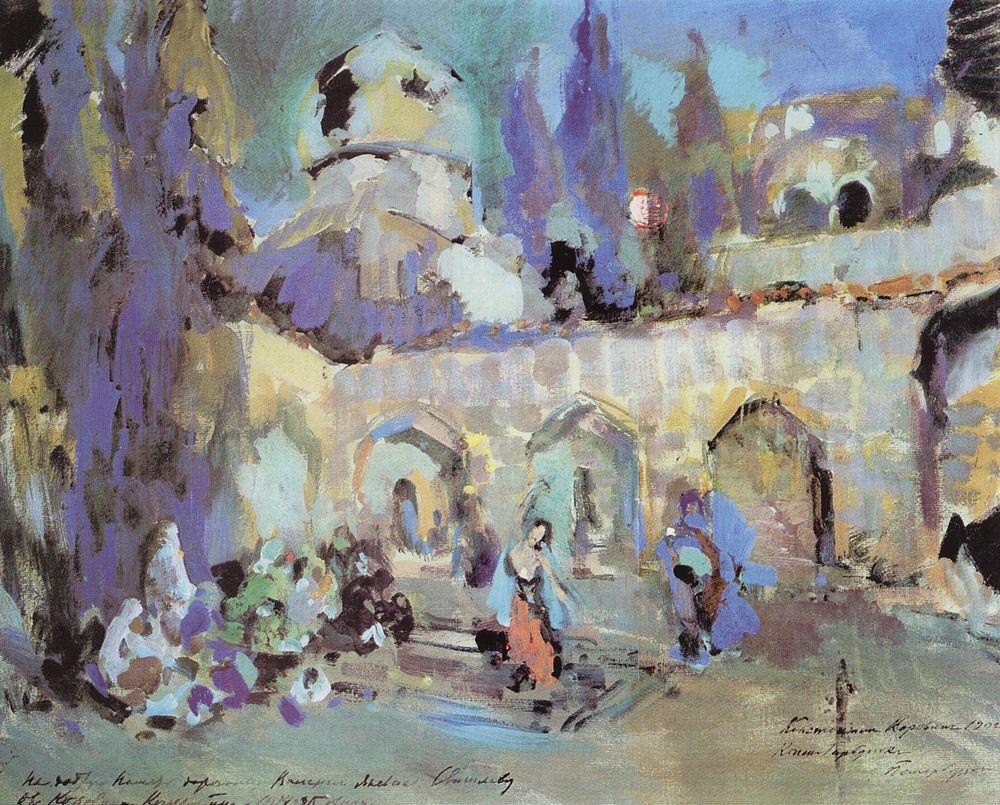

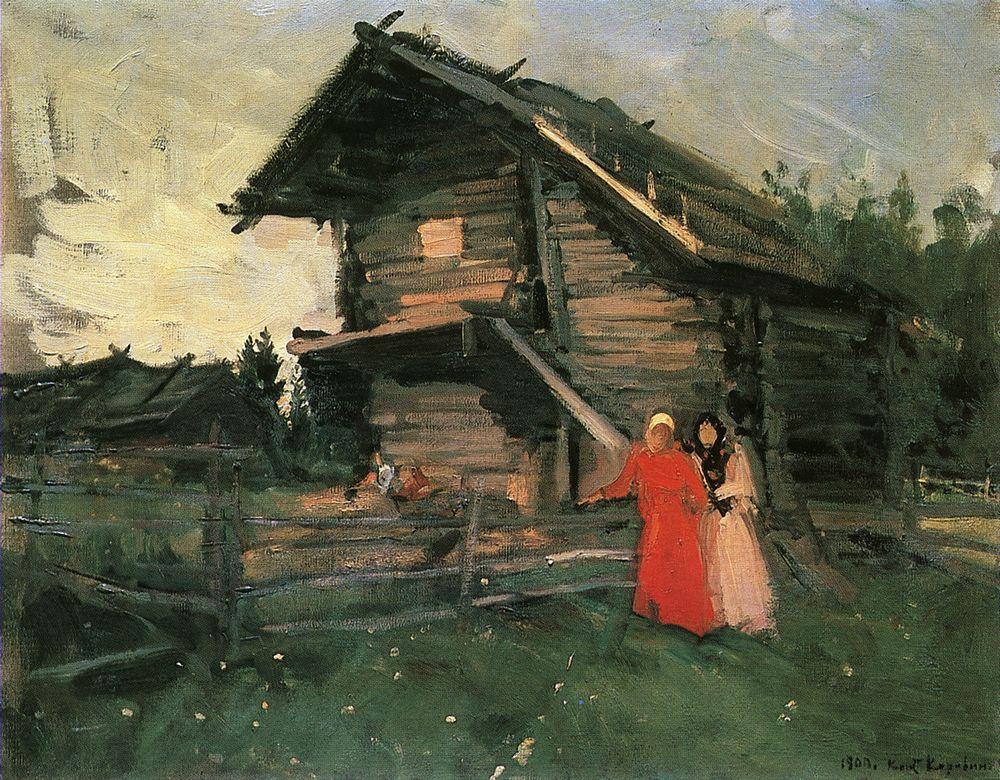

Travels With Savva and Organization Man

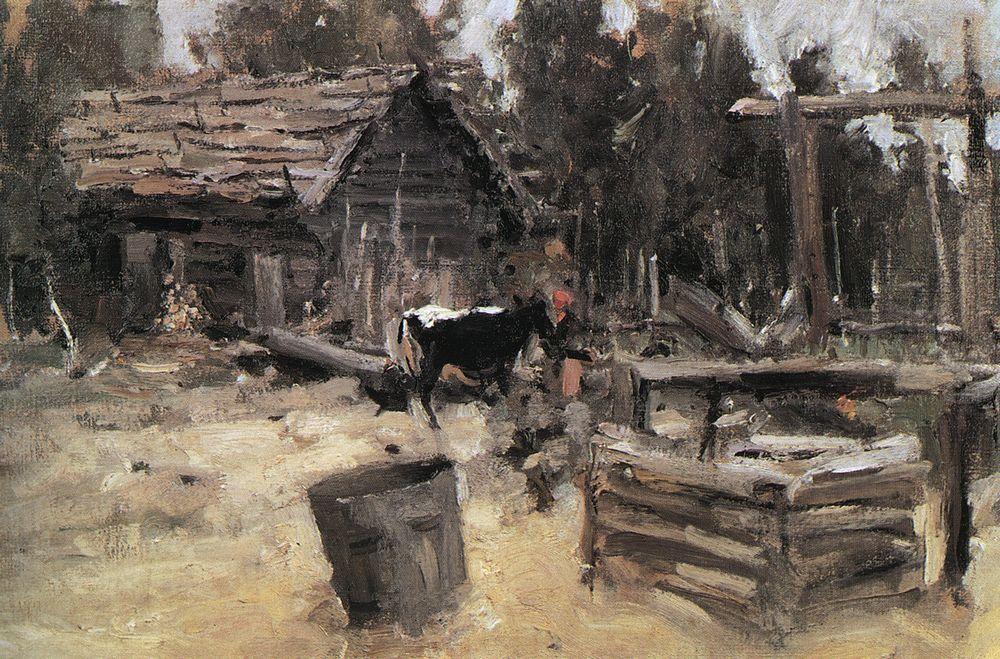

In 1888 Konstantin traveled with Mamontov in Italy, Spain and extensively in Russia the Caucasus and Central Asia. All became subject matter for his paintings. He also exhibited with the artists known as the “Peredvuzniki”. More formally “The Society for Itinerant Art Exhibits” this group, formed in 1870 shared with the Abramtsov Colony a passion for everyday subject matter; peasants, wheat fields, pine forests and steppes. It was a nationalist movement reacting against what they saw as the academy’s European and classical bias. Their interests were not limited to art, they also agitated for political and social reforms. There were similarities with the French Realist movement that preceded Impressionism and lead Gustav Courbet to get in trouble with the government over his participation in the Paris commune of 1871. Surprisingly, given the Tsar’s extensive security apparatus the Peredvuzniki continued their activities until the revolution.

By the turn of the century Konstantin was also active with the “Mir iskkusstva” (Art World) group. Associated with a magazine of the same name they advocated for traditional folk art and the Rococo art of the 18th century. Watteau and Matruschkas seem like strange bedfellows but they attracted a number of well known personages besides Korovin including, Leviton, Stravinsky, and Diaghilev. They seemed a lighthearted group and the produced some delightful work.

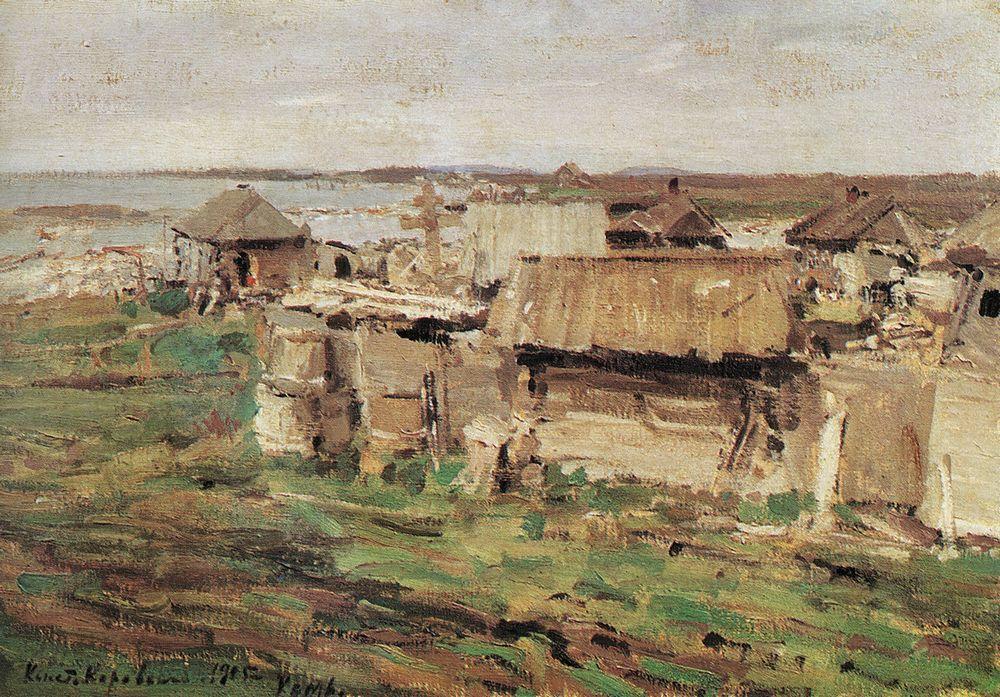

Snow and Show Business

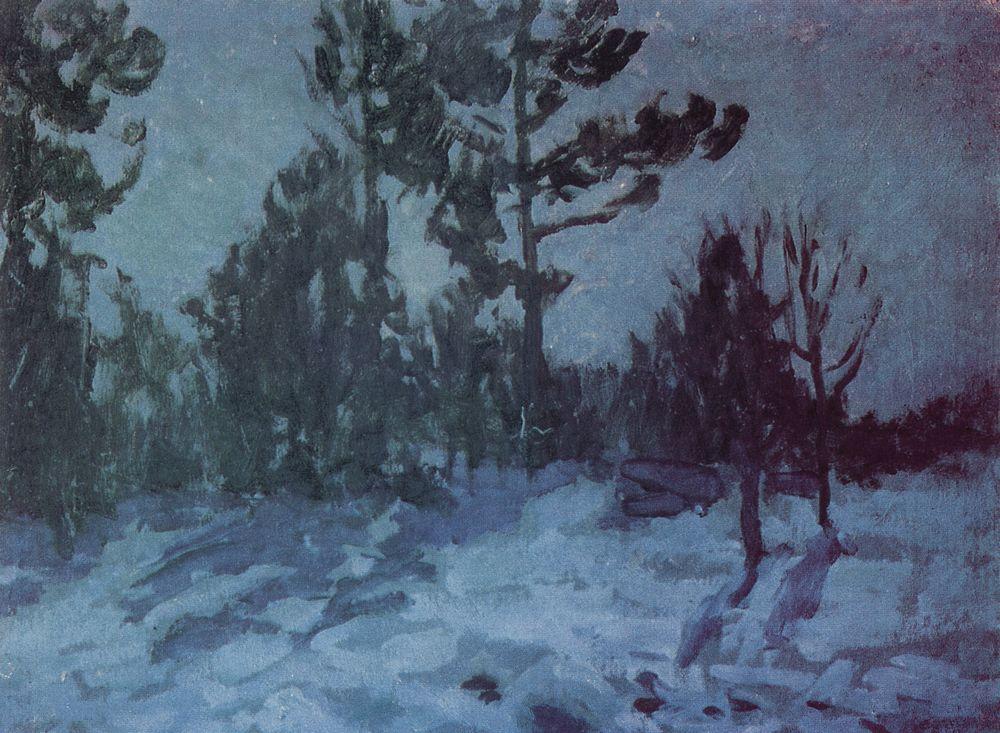

Inn 1888 and again in 1894 Konstantin traveled in Northern Europe. Valentin Sérov accompanied him on the second trip which was facilitated by the completion of the Northern Railway. The subarctic landscape had a great impact on him and inspired a number of his paintings. His interest in the North led to design commissions for the “Far North” pavilion at the All Russia exhibit in Nizky Novgorod in 1896 and at the Paris exposition in 1900. In addition to gold medals he received the Legion of Honor for his work on the exposition.

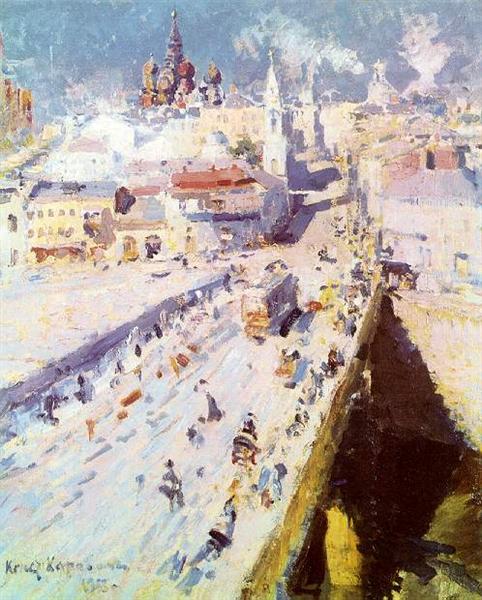

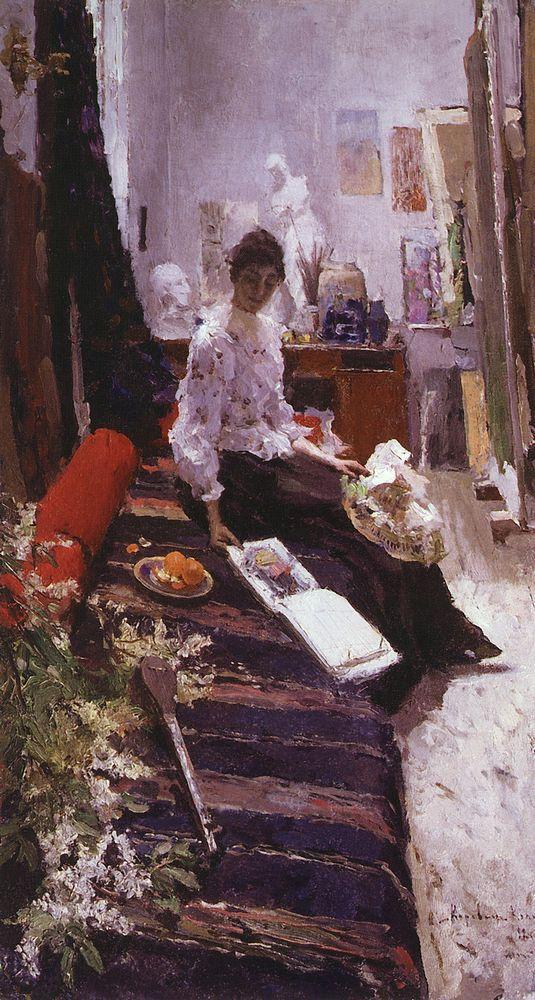

The first decade of the Twentieth century saw him working in the theatre, producing memorable set designs for the Marinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg and Stanislavsky productions in Moscow. In 1905 he was recognized as “Academician of Painting” and from 1909 to 1913 was a professor at his alma mater The Moscow School of Painting Sculpture and Architecture.

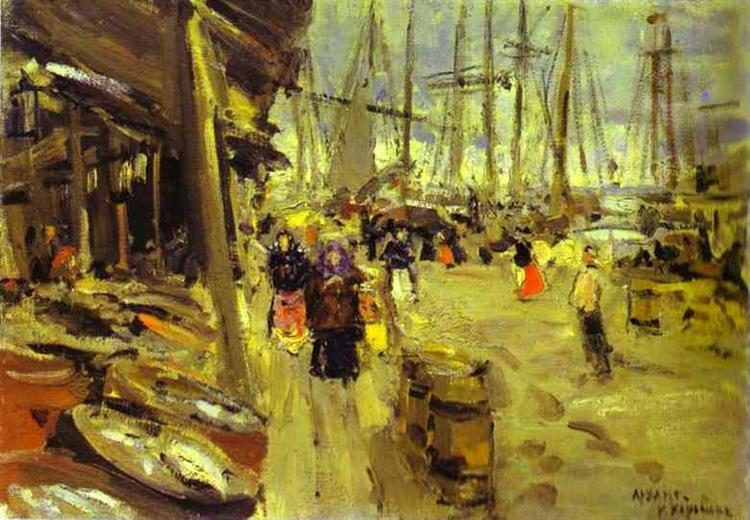

He had not forgotten Paris and continued to visit. Parisian themes appear frequently in his paintings at this time.

Konstantin Korovin – Snowscapes

The winter landscapes of Konstantin Korovin

War and Revolution

During the First World War Konstantin worked for the Russian Army as a camouflage consultant and frequently visited the front. He continued to paint though believing that after the horrors of war the world would have an even greater need for art. After the war he returned to the Moscow theatre and his easel. In the twenties he was holding successful exhibitions in Moscow. His health was beginning to fail and although he longed to remain at his country house, after the Russian Revolution he found himself involved in the politics of art. He was appointed to several bureaucratic positions including the Commission for the Preservation of Monuments. Perhaps he tried to preserve the wrong one, because in 1923 the commissar of education “suggested” that he best travel abroad for his health.

He decided to return once again to Paris and delivered his large inventory of paintings to his gallerist in anticipation of exhibitions and sales in France. The gallerist and the paintings disappeared though and Konstantin and his son found themselves close to penniless in Paris and unable to return home. He had been a popular success in Russia but tastes in Paris had moved on and Impressionism was not in fashion. He supported himself by producing picturesque Russian landscapes and Parisian street scenes for the tourist trade. Quite a comedown from his glory days in Moscow.

Sainte Geneviève des Bois

He lived ten more years in Paris so perhaps the Commissar was right. On 11 September 1934 he finally succumbed to his heart ailments. He was buried in a Parisien suburb in the Sainte Genevieve des Bois Russian Cemetery. He was survived by his son who had something of a painting career of his own but committed suicide in 1950.

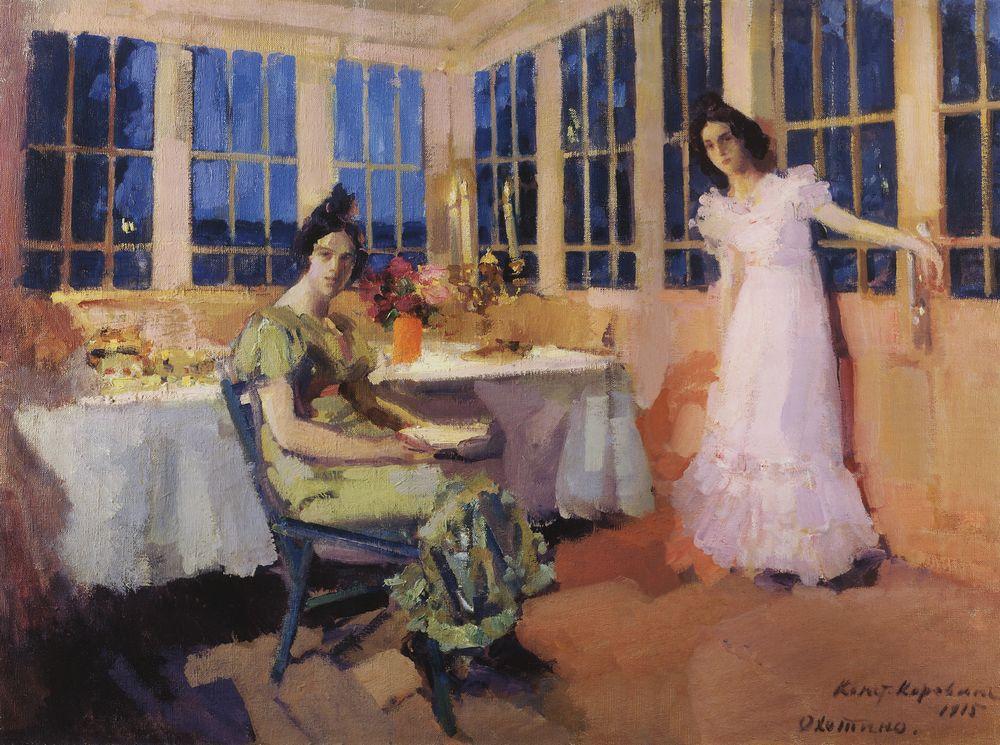

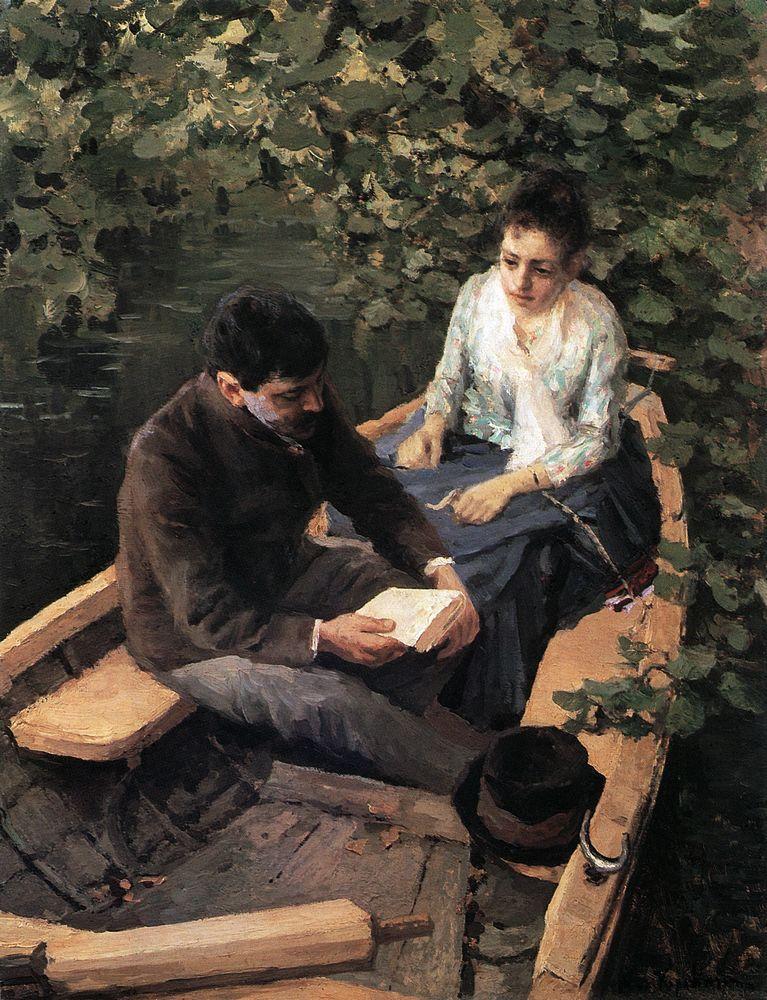

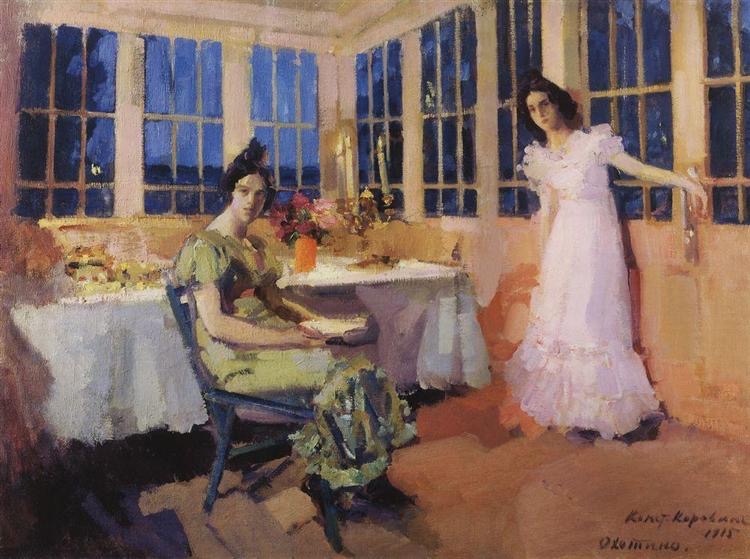

Konstantin had lived an eventful life. A leader of the Russian art world, and a giant of the world theatre, he had survived war and revolution, the pandemic of 1918, poverty and family tragedy. But I prefer to think of him on his veranda in Okhotino, painting pretty women, drinking vodka and talking with his friends about politics, art, color and Paris.